Spring, 2016

Friends of Gatoto,

As generous supporters of Gatoto in Nairobi, you might be interested in a few words about my recent trip to visit the school.

I traveled to Gatoto because it seemed too good to be true. Can an independent pre-K through 8th grade school created more than 20 years ago by slum dwellers really educate 1,000 students—an equal number of boys and girls, coming from a broad variety of religious and tribal backgrounds, on just $300,000 per year? On that tiny budget, does it really give them a hot meal every day and financial support to continue on to high school and university? In early May, having previously studied Gatoto’s financials and other materials, I spent four days on the campus to answer these questions.

My answer is, Yes. Gatoto is a rare gem.

Gatoto is located in Mukuru kwa Reuben slum, a harshly functioning community of 80–90,000 people surrounded by an industrial park on the outskirts of Nairobi. It is hard for Americans to imagine its conditions. In the rainy season, mud is everywhere. Waste of all kinds is almost as common. Public sanitation is limited, and electricity is scarce.

Dwellings are like deteriorating storage units—cramped, windowless sections of large, rotted metal-sided buildings. Some have mud floors; some concrete. Light is more likely to come from a kerosene wick than a light bulb. Theft is a constant threat, and violent crime is common. Girls and young women are particularly vulnerable.

Amid all of this, Gatoto stands as an oasis of hope and inspiration. The campus is secure and trash-free. The buildings are a mix of newer masonry structures and older metal-sided buildings. There are toilets, housed in separate structures, and playing fields where students play. In class, students are strikingly attentive. At breaks, they kick homemade soccer balls, jump rope, talk. Every day, they are given a simple, hot lunch. The students are very poor, but at Gatoto, they are safe, and they are learning.

I spoke with many members of the Gatoto community, including the school’s administrators, its faculty, the Board of Directors, leaders of the PTA, the auditor, the architect, and an ex-pat Irish math teacher who volunteers three time a week, tutoring both students and faculty. I spent time with many students of a range of ages, both inside classrooms and out.

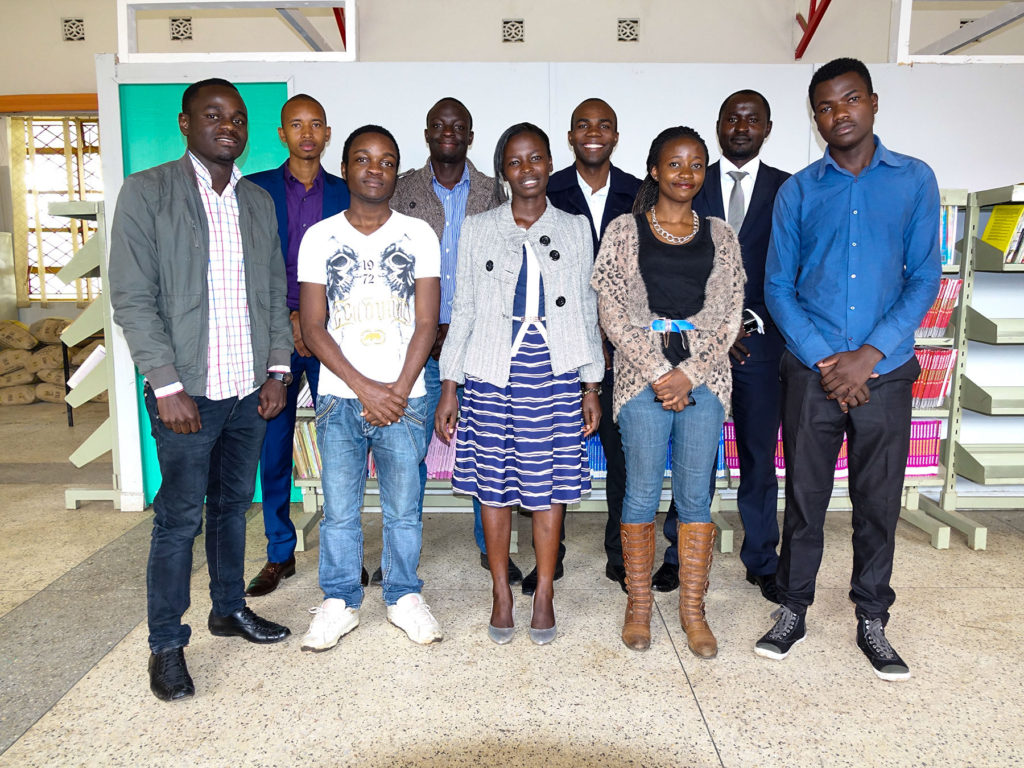

Most compelling was the time I spent with these nine graduates, six who are currently in university, three who have earned their degrees. Their average age is probably 20 or 21. A truly impressive group of appropriately polished young adults, they would make any American school proud.

Many emphasized their impoverished origins, of being from the slums, of having “nothing, nothing”—as if their current lives made their pasts seem impossible. Most received scholarships from Gatoto to attend Gatoto itself, and then for high school and university. One said that Betty, the school’s director, and Joseph, the head teacher, visited him when he was away for high school, simply to see how he was doing. Another described being taken under the school’s wing after his mother and father suddenly died, saying Gatoto is his mother and his father now.

The graduates are alert and perceptive. They looked me in the eye and conversed in confident, good English. Sometimes their tone was almost pleading, as if to say, “Do you understand what I’m saying? We had nothing. Now we have futures.”

One exchange with the Gatoto alums shows the precariousness of life in the slum—and the opportunity the school represents.

I asked, How many of you have former classmates from Gatoto whose lives were changed by early pregnancies? Seven raised their hands.

I asked, How many of you have former classmates who have died violently? Five.

And I asked, How many of you have former classmates from Gatoto who went on to university? They all raised their hands.

Misfortune, a life spent continuing the cycle of poverty, even a life ended early may await some of Gatoto’s students. But so too do opportunity, hope, and the dream of lifting oneself and even one’s family out of the slum.

Gatoto has been educating students, saving and transforming lives, for 22 years. Having taken time to see it for myself, to conduct my own skeptical due diligence, I believe it will continue to do so for many more years to come. I’m grateful for the opportunity to help it along.

We’ll be in touch as the year progresses. In the meantime, if you have any questions or comments, please let me know—and please keep Gatoto in mind as you contemplate your charitable giving in 2016.

Sincerely,

Peter Edwards

Member, Board of Directors

American Friends of Gatoto